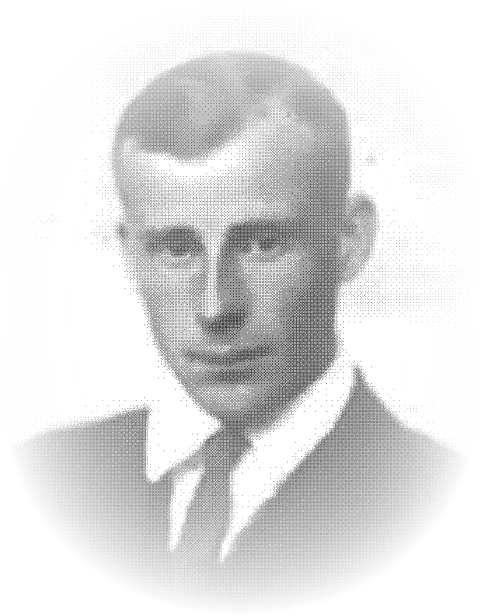

Yuri Ivask became an integral part of Russia in exile and a witness to the unnoticed generation of Russian literature abroad.

There are two of you — a poetry lover and an archivist. (poet Marina Tsvetaeva)

Yuri Ivask never stopped writing and managed to pass the baton to the poets of the Third Wave of Russian emigration. For example, he met Joseph Brodsky and was involved in the fate of Dmitry Bobyshev. The letters from Georgy Adamovich, Igor Chinnov, and Marina Tsvetaeva are testimony to Ivask’s humanity:

Apart from everything, it is cozy with you, being with you is like being with myself. You give me just enough warmth to rejoice when we meet, and when we say goodbye — not to regret, or — regret a little bit. Thank you for everything: for the cold that we shared — though I didn’t even notice, for the dark windows where we stood together, for the warmth we felt in the first — it didn’t even matter! and there was no time to look! — café we came across, for the gifted pencil, for the promised towel. (February 27, 1939)

Yuri Ivask was born in Moscow to an Estonian-Russian family. At the beginning of the Russian Civil War, he was taken by his parents to his ancestral homeland.

I was thirteen years old when we moved to Estonia, where I stayed for more than 20 years. A thirteen-year-old boy is a blank slate. But even in my adolescence, I knew all too well: I was Russian and hardly ever talked to Estonians. I permanently lost the Russian soil under my feet, but my foundation was the Russian language, and my soul was made of the Russian language, Russian culture, and Russian Orthodoxy.

He was a member of the Revel Poets’ Guild and studied at the University of Tartu, Hamburg University, and Harvard. Later he taught Russian literature at many universities in the United States. In 1953, he compiled and published the first anthology In the West, which brought together poets of the First and the Second Waves of Russian emigration. After becoming editor-in-chief of the New York literary journal Experiences (Opyty), Yuri Ivask continued to witness and preserve. Thanks to him, Boris Poplavsky’s prose, Marina Tsvetaeva’s letters to Anatoly Steiger, and Vladimir Nabokov’s memoirs were published for the first time.

Having learned that a samizdat collection of his poems was published in the Soviet Union, he dared to come back as a tourist:

In the summer of ’83, I ended up spending two weeks in Leningrad and Moscow. I flew there from Paris, with a French tour group. I was blown away by St. Petersburg in Leningrad. An unforgettable morning on the Spit of Vasilievsky Island. That monstrously wide, hostile, but gorgeous Neva. I thought my heart was going to shatter from that happiness.

Yuri Ivask, a poet of broad range and widespread interests (which included ancient Mexican religion and 17th-century metaphysical poets, to name just a few), summed himself up in the novel in verse Homo Ludens (The Playing Man).

The Playing Man seeks to bring humanity, trapped in hell, closer to heaven. (philologist Temira Pachmuss)

Ivask died in 1986 in Amherst, the hometown of his favorite poet, Emily Dickinson.

Korolev Popova|Korolev Popova

Sing — sang — sung,

Drink — drank — drunk,

Field — field — field,

Shoot — shot — shots,

Fall — fell — fallen.