If émigré literature produced just Poplavsky alone, that would already be enough to exonerate it in all future trials. (writer Dmitry Merezhkovsky)

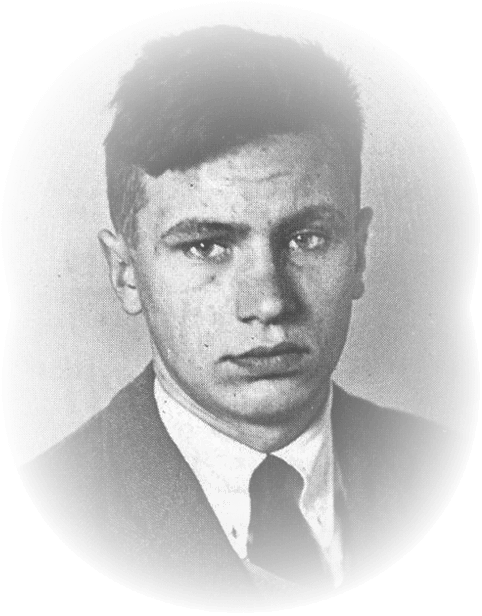

Poplavsky’s talent was universally recognized in Russian émigré circles, where Boris was kind of an enfant terrible: a God-seeker and God-denier who flirted with death, always sporting sunglasses.

He never took off his sunglasses, so he didn’t have a gaze. (writer and memoirist Nina Berberova)

In Istanbul, seventeen-year-old Poplavsky joins the Tsargrad Poets’ Guild. In his first years in Paris, he considers himself an artist, attends the famous art academy, and goes to Berlin to master the craft of portrait painting. But his passion for literature and reflection leads him to the Faculty of Philosophy at the Sorbonne. A regular in Montparnasse, an essential part of its landscape, Boris Poplavsky went all-in — and decided that being a penniless clochard was better than being an unskilled laborer without the energy and time for literature. So he was desperately poor and wrote a lot. He was often seen waiting in line for unemployment benefits.

Poplavsky’s daily budget was seven francs, three of which he gave to his friend. Dostoevsky was to Poplavsky what Rockefeller is to me. (poet Vladislav Khodasevich)

Outwardly, Boris Poplavsky’s career was flourishing. His poetry and prose regularly appeared in the émigré press — the first few chapters of his novel Apollon Bezobrazov were printed in an émigré magazine. Flags, his first poetry collection, was a major event. But his personal and private life was on the brink of catastrophe. Poplavsky drove himself to nervous breakdowns with fanatical prayer vigils, binge-drinking, and fights; he would fall madly in love and scold himself fervently for the weakness of body and spirit. Like most Russian emigrants, Poplavsky sought an outlet for his anguish over Russia:

...if Russia does go past individuality and freedom (that is, past Christianity with God, or without God), we will never return to Russia, and eternal love will then be in eternal conflict with Russia...

One young man, determined to commit suicide, decided out of cowardice to take his associate with him — which happened to be Boris Poplavsky. He died of a drug overdose at his creative peak at the age of thirty-two.

Together with him went silent that last wave of music which, out of all his contemporaries, he alone would hear. And within the literary arguments, which he would often become caught up in, would typically be hidden a singular inextinguishable misunderstanding which would separate him from his conversational companions: he spoke about poetry, while they went on about how to write poems. (writer Gaito Gazdanov)

Tequilajazzz|Tequila-jazzz

On a summer day over the white pavement

Japanese lanterns were hanging.

The trumpet voice mumbled over the boulevards,

on big poles the flags were dreaming.

It seemed to them that somewhere the sea was close,

and along them a wave of heat was running,

the air slept, not seeing dreams as Lethe.

Pity of the flags overshadowed us.

The boat’s frame appeared to them

Black smoke that tenderly flew away,

and a prayer over the boundless wave

of the ship’s music on Christmas Eve.

The quick flight on the mast in the ocean,

the noise of salutes, the cry of black sailors,

and the enormous lowering down over anchors

in the hour of the fall of the body in mourning clothes.

First the flag glistens over the horizon

and cheerfully whirls to the flashes of cannons

and last of all sinks among the debris

and still with a wing beats about the water.

Like the soul, which leaves the body,

like my love for You. Answer me!

How many times did you wish on a summer’s day

to wrap yourself up in a flag and die.

Translated by Belinda Cooke and Richard McKane